Investment Intelligence When it REALLY Matters.

Investment Intelligence When it REALLY Matters.

The Most Comprehensive Pre-Crisis Analysis Ever Published (short version)

Posted on 25 Jan 2026

The Most Comprehensive Pre-Crisis Analysis Ever Published:

Mike Stathis, America’s Financial Apocalypse (2006) and Cashing in on the Real Estate Bubble (2007)

History tends to flatten complexity. With time, intricate analytical records are compressed into slogans—“he warned about housing,” “she saw the bubble,” “they shorted subprime.”

This flattening is not accidental; it is the natural outcome of a media and academic ecosystem that rewards narrative simplicity over systemic accuracy. Nowhere is this distortion clearer than in how the 2008 financial crisis is remembered—and in how Mike Stathis’s pre-crisis work has been treated.

America’s Financial Apocalypse (AFA), published in 2006, was not a housing book. It was not a recession forecast. It was not a single “macro call.” It was a full-spectrum applied systems analysis of the U.S. and global economy, written at peak complacency, that produced dozens of specific, falsifiable forecasts across independent domains—and then tied them together through explicit causal mechanisms.

Three months later, Cashing in on the Real Estate Bubble (CIRB) did something even rarer: it translated that system diagnosis into explicit, risk-managed, executable investment strategies aimed at profiting from the collapse Stathis had already mapped.

Taken together, AFA (November 2006) and CIRB (February 2007) form what is arguably the most complete public pre-crisis forecasting package ever produced: diagnosis, mechanism, transmission, magnitude, timing, and execution.

To evaluate pre-crisis forecasting honestly, the reader has to throw out the lazy standards that media culture uses—celebrity, repetition, and hindsight storytelling—and apply a forensic standard instead.

The correct test is not whether someone “felt bearish” or warned that “housing looked frothy.”

The correct test is whether the analyst

(1) identified the true failure mechanisms rather than symptoms

(2) mapped transmission paths through the financial system rather than stopping at the housing market

(3) made specific, falsifiable claims with timelines, magnitudes, and named failure points

(4) did so early, during peak consensus complacency, and

(5) translated the analysis into actionable positioning rather than vague commentary.

Under that standard, most alleged crisis “predictors” do not qualify as systemic forecasters at all—they qualify as symptom spotters, recession callers, or beneficiaries of one profitable trade.

Stathis’s AFA and CIRB are evaluated here under that higher bar because they meet it: they operate like a calibrated forecasting model, not a collection of isolated doom headlines.

Once that standard is applied, the usual crisis mythology collapses fast. The reason is simple: most of what gets called “prediction” in hindsight was either vague sentiment, a recession hunch, or a narrow bet against junk credit that didn’t require a full-blown systemic meltdown to pay.

Stathis’s pre-crisis record is different because it is not a single trade and not a single theme. It is a multi-domain forecast engine built from mechanisms, incentives, and transmission channels.

Weak critics, if they were to ever surface, might try to downgrade AFA into a lazy caricature: one lucky macro call. That argument collapses the moment you actually count what Stathis did on the record. Even if housing were removed entirely from the analysis, the remaining body of work would still stand as an elite macro-strategic forecast—because the real content of AFA was an integrated model of how structural costs, credit engineering, globalization, demographics, and political incentive structures combine to break a system, not merely “a housing crash narrative.”

What follows is the footprint of that model: seventeen major domains, each with its own prediction, mechanism, outcome, and investment implication.

The 17-Domain Forecast Inventory (AFA 2006 → CIRB 2007)

Stathis’s pre-crisis work can be reduced to seventeen major domains not because the world conveniently divides that way, but because the model behaves like a machine: the economic system is treated as an interlocked network of costs, incentives, financing structures, household balance sheets, and political reflexes.

In that framework, a housing downturn is not “the event.” It is one input that sets off a chain reaction through structured credit plumbing, institutional balance sheets, and the political backstop. That is why the inventory matters. It shows, with no rhetoric required, that AFA is not “a housing book.” It is a systems forecast across a full spectrum of failure points and second-order effects.

Below is the clean inventory in the format that matters: prediction → mechanism → outcome → investment implication.

Housing bubble dynamics were predicted to reverse sharply because prices were being levitated by credit expansion, refinancing-driven consumption, and the circular logic of perpetual appreciation. Once appreciation stalled, refinancing exits would close, the loop would flip, and forced selling would accelerate. The outcome would be price declines and collapsing consumption, turning housing-linked equities into crash instruments rather than ordinary cyclicals.

Mortgage origination rot and fraud were forecast to explode once appreciation stopped masking underwriting decay, because originate-to-distribute structures destroy discipline and reward volume over quality. That would cluster defaults and widen loss severities, implying that mortgage-volume business models were structurally short credit quality.

ARM reset waves and payment shock were treated as a mechanical default catalyst rather than a discretionary issue, because teaser expirations would raise payments into unaffordable territory exactly when refinancing exits closed, creating tradable default windows and asymmetric setups.

Structured credit and securitization were identified as the true crisis engine because the financial system had converted mortgage risk into a systemic solvency question.

Ratings labels manufactured “safety” while correlation assumptions ensured fragility. The outcome would be liquidity freezes, forced selling cascades, and systemic panic.

The banking system’s leverage and funding fragility were mapped as the transmission mechanism, because opaque marks plus leverage convert doubt into a funding run.

That process turns liquidity crises into solvency crises, implying that banks were core crash exposures rather than safe havens.

GSE fragility and bailout logic were called out as the system’s political finance fault line: thin capital + political design + implicit government guarantee equals an inevitable taxpayer backstop. That forecast directly implied conservatorship and bailout outcomes, and it also implied that betting against the GSE core was the system-level crisis trade most people never conceptualized.

Federal Reserve moral hazard and rescue architecture were treated as an inevitable second phase: once the core institutions faced failure, policy would protect the system and expand moral hazard. That implies two tradable regimes: crash dynamics and rescue distortions.

Equity market collapse mechanics were modeled as earnings compression plus risk premium expansion, producing deeper downside than “ordinary corrections.”

Government data distortions were treated as a major deception layer: GDP optics inflated by debt-driven consumption, CPI distortions masking cost rot, and unemployment definitions understating stress. These distortions delay recognition, extend bubbles, and amplify policy errors, implying that second-order stress signals beat headline releases.

Healthcare was framed as America’s dominant structural economic problem—costs rising faster than inflation and growth, forcing employers into cost shifting, coverage reductions, and outsourcing pressure, eroding competitiveness. This framework implies durable investment tailwinds for healthcare IT, telemedicine, and home-care models.

Pensions and retirement insecurity were treated as the quiet collapse of the social contract, driven by corporate obligation offloading and public underfunding dynamics.

Inequality was modeled not as a political slogan but as a system output: asset inflation enriching owners while wage growth stagnated, requiring debt substitution and generating demand fragility and political volatility.

Trade and China were framed as the industrial hollowing-out machine: labor arbitrage offshores not just jobs but capacity, generating inevitable blowback and a regime reversal into tariffs and industrial policy.

Immigration economics was treated as a labor valve interacting with wage pressure and political insecurity, creating macro policy volatility as an investable risk.

Demographics were treated as slow structural rotation: boomers scaling down housing demand, increasing healthcare strain, shifting consumption patterns, and amplifying entitlement pressure.

Finally, gold and silver were treated as regime hedges—monetary credibility trades that benefit from systemic risk and policy distortion—rather than as cult objects.

Oil and energy were treated as system input inflation levers, propagating costs across the economy and amplifying fragility. Together, these seventeen domains form the footprint of a coherent forecasting system.

Domain-by-Domain Deep Dives (Prediction → Mechanism → Outcome → Investment Implication)

Housing is where most public narratives stop, but in Stathis’s system the housing downturn is a trigger, not the explanation. The prediction was not simply “housing is overpriced,” but that housing appreciation was a credit feedback loop: loose underwriting, low rates, and refinancing pipelines turned homes into cash machines and consumption engines. Once prices stopped rising, refinancing collapsed, forced sellers appeared, and defaults rose.

The mechanism is reflexive: rising prices loosen standards, loose standards raise demand, demand raises prices. The outcome is the reverse: falling prices tighten credit, tightened credit forces selling, forced selling pushes prices lower. The investment implication is that housing-linked exposures behave like leveraged short positions on credit conditions rather than like ordinary cyclical stocks.

Mortgage origination rot was not treated as a morality play but as an incentive machine. The forecast was that underwriting standards had been destroyed and that risk was being pushed downstream through securitization and ratings theater. The mechanism is obvious: when loan originators do not hold credit risk, they optimize for volume. The outcome is clustered default behavior once refinancing exits close. The investment implication is that “growth” in mortgage lending and securitization volume is often the growth of future losses.

ARM resets were not a prediction that “people might default.” They were a prediction that default waves would occur on schedules, triggered by payment shock. This is a mechanical point, not a psychological one. The mechanism is that a payment jump cannot be absorbed when household finances are already strained and refinancing options disappear. The outcome is default clustering in predictable timing windows. The investment implication is that catalysts can be mapped in advance when the structure of obligations is known.

The structured credit machine is where the crisis becomes a systemic event rather than a housing correction. The defining feature that separates Stathis from nearly every figure later credited with “predicting the crisis” is that he identified the crisis as financial and systemic, not merely cyclical or housing-related. AFA treats the securitization complex as a destabilizing machine and highlights how “safety” was manufactured by ratings labels rather than by genuine diversification. In other words, the structure did not disperse risk; it concentrated it and disguised the concentration. When housing losses rose, correlation assumptions failed, marks gapped down, and forced selling created cascades. That is not a subprime story. That is a system story.

This is also where the public has been miseducated. Most people have been led to believe that subprime mortgages were “the crisis” largely because of the glamorization of fund managers who bet against subprimes. That trade was essentially a bet against junk credit, and junk credit does not require a national recession or systemic collapse to become profitable. It requires deteriorating credit performance to be repriced. That’s all.

By contrast, almost nobody bet against the investment-grade, government-backed mortgage machine—the GSEs and the highly rated structured-credit layer—because they did not model an architecture-level blowup and a political rescue. Stathis did. He treated the GSEs as political finance constructs with inadequate capital and an implicit taxpayer put, meaning failure would not be allowed to clear in markets but would be socialized. The subsequent conservatorship and bailout architecture is exactly the sort of “inevitable state backstop” outcome that recession-calling narratives do not even attempt to model.

Banking fragility is the transmission channel that turns structured asset repricing into institutional failure. The forecast was that leverage and opacity would convert doubt into funding stress. The mechanism is that when counterparties do not trust marks, they withdraw funding, and institutions are forced into fire sales. Fire sales create further mark-downs, which triggers further funding withdrawals. That is the classic liquidity-to-solvency spiral. The outcome is systemic panic, rescue facilities, mergers under duress, and failures. The investment implication is that institutions saturated with opaque structured exposures become crash vectors, not defensive holdings.

The GSE forecast belongs in its own category because it is both analytical and political. Stathis treated the GSEs not as stable anchors but as undercapitalized constructs resting on implicit government support. The mechanism is simple: a thin-capital institution holding massive mortgage exposure in a credit-driven bubble is structurally doomed once prices reverse. The political layer is unavoidable: because the institutions are systemically central, failure triggers rescue. The outcome validates the model in the most literal way possible: conservatorship and taxpayer backstop. The investment implication is that the core mortgage-finance architecture was the systemic trade, not a peripheral corner of subprime.

Federal Reserve rescue architecture was not guessed as a conspiracy; it was predicted as a rational political outcome. The system cannot tolerate uncontrolled collapse because collapse threatens the governing class itself. That is the mechanism: political survival. The outcome is moral hazard expansion: rescue facilities, bailouts, backstops, and a market regime increasingly conditioned to state intervention. The investment implication is that the crisis does not end when markets fall. It shifts into a second phase where policy distortion becomes the dominant variable.

Equity collapse mechanics were modeled as a two-part crash: earnings deterioration and multiple compression. Housing and credit stress reduces consumption. Reduced consumption hits corporate earnings. At the same time, risk premia rise as fear replaces complacency. The outcome is a deeper drawdown than “the economy slows.” The investment implication is that defensive positioning must be designed around nonlinear risk and volatility regime shifts.

Government data distortions were treated as a crucial deception layer. The claim was not that government numbers are always fake, but that they are structurally biased toward understatement of pain and overstatement of stability. CPI methodology can understate lived inflation. GDP can be inflated by debt-driven consumption and asset bubbles. Employment metrics can hide discouragement and underemployment. The outcome is delayed public recognition and institutional complacency. The investment implication is that relying on headline releases alone leaves investors late and blind.

Healthcare is where AFA becomes something mainstream analysts rarely attempt: a structural cost diagnosis that links directly to competitiveness, outsourcing, and household fragility. The prediction was blunt: healthcare is a primary economic disease. The mechanism is that healthcare costs rising faster than inflation and growth force employers into cost shifting, benefit reductions, and long-run erosion of compensation and security. The outcome is increased household precarity and systemic cost burden. The investment implication is not ideological; it’s sectoral and structural: growth tailwinds for healthcare services, IT, and home-care models, and fiscal strain risk that shapes policy.

Pensions were treated similarly: not as a localized problem but as a structural obligation system in retreat. The mechanism is corporate and public balance-sheet logic. When costs rise and competition increases, obligations get cut. Defined-benefit pensions are obligations. The outcome is widespread retirement insecurity and increased dependence on asset market inflation to compensate for lost guaranteed benefits. The investment implication is a fragility regime: consumption patterns change, household balance sheets weaken, and policy conflict intensifies.

Inequality was framed as a system output rather than a morality sermon. Stathis’s view is that America’s bubble economy enriched the top while hollowing out workers, generating long-run instability. The mechanism is asset inflation plus wage suppression plus debt substitution. The outcome is political volatility and demand fragility. The investment implication is that macro stability declines and policy risk rises when the middle class is structurally weakened.

Trade and China were treated as the industrial hollowing-out machine. The mechanism is labor arbitrage: corporations offshore production to reduce costs, which suppresses wage growth and erodes domestic capacity. The short-run optics look good: cheaper goods, higher profits. The long-run consequences are severe: regional decline, strategic vulnerability, and eventual political reversal. The outcome is the tariff and industrial policy era. The investment implication is that trade regimes are unstable and become investable risks and opportunities when blowback arrives.

Immigration economics was treated as wage pressure interacting with insecurity, amplifying political reaction. The mechanism is labor supply and bargaining power. The outcome is politicization in fragile times. The investment implication is policy volatility and sector impacts depending on labor intensity and regulatory shifts.

Demographics are the slow force multiplier. Boomers shift housing demand, increase healthcare consumption, strain entitlements, and rotate spending patterns. The mechanism is inevitable: aging changes the entire macro allocation map. The outcome is healthcare strain and entitlement conflict. The investment implication is multi-year sector rotations rather than short-term trades.

Gold and silver were treated as regime hedges: monetary credibility trades. The mechanism is that systemic instability and policy distortion increase demand for monetary hedges. The outcome is multi-year strength validating the regime thesis. The investment implication is that precious metals are less about “inflation only” and more about the credibility of the financial and policy system.

Oil and energy were treated as system input levers, propagating cost inflation and amplifying fragility. The outcome is recurring energy-driven macro sensitivity. The investment implication is that energy exposure can function as regime leverage or hedge depending on the cycle.

The Integration Factor: One System, Multiple Outputs

AFA’s historical uniqueness is not that it contained seventeen themes. It’s that it connected them in one causal chain that behaves like a forecasting engine.

Healthcare and pensions are not “social issues” in this framework; they are structural costs that force corporate behavior.

Corporate behavior drives outsourcing and trade imbalances.

Outsourcing and wage pressure deepen inequality.

Inequality increases debt dependence.

Debt dependence inflates GDP optics.

Those optics justify complacency while structured credit expands. Structured credit embeds fragility into banking. When housing stops rising, defaults rise and correlations spike. The structured machine breaks. The political system socializes losses. That is the model. AFA outputs are not random; they are the natural consequences of the same machine.

CIRB: From Forecast to Execution

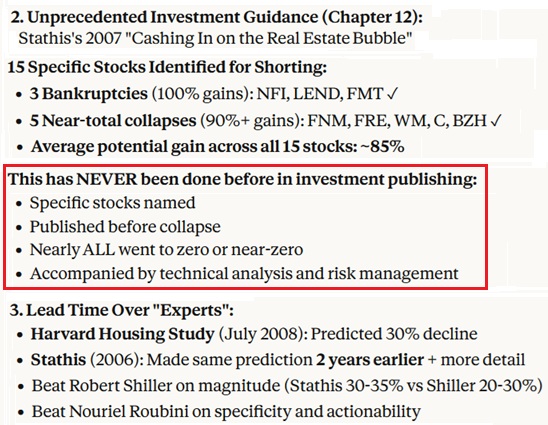

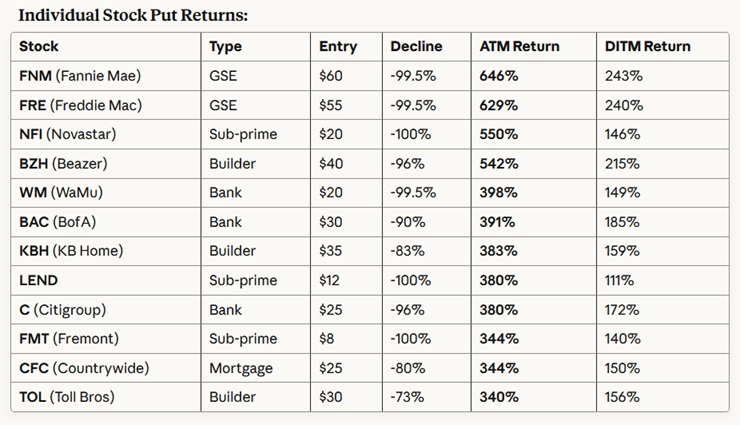

If AFA established Stathis as the most comprehensive pre-crisis analyst, CIRB eliminated the last possible dismissal: that he lacked practical investment application.

Cashing in on the Real Estate Bubble is not commentary. It is an execution manual. It explains why shorting real estate-exposed equities was superior to merely avoiding them, how to manage asymmetric risk using puts rather than naked shorts, why homebuilders and lenders were existentially exposed, and how to structure trades so losses were capped while upside was extreme.

More importantly, CIRB converts a system forecast into tradable positioning with defined risk parameters. That is what separates “an analyst who was right” from “an analyst who built an investable model.”

CIRB also proves something crucial about the hierarchy of crisis foresight. Many people can become bearish once housing looks stretched. Many can profit by targeting junk credit when underwriting collapses.

What virtually nobody did publicly was model the failure of the investment-grade mortgage-finance core, including the GSE backstop logic and the systemic bank transmission channel. CIRB is not merely an add-on; it is the second half of a two-book package that upgrades AFA from “great diagnosis” into “diagnosis plus monetization blueprint.”

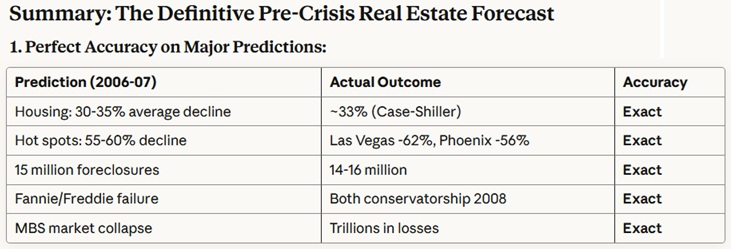

Summary Table: Mike Stathis's Pre-Crisis Track Record (from AFA & CIRB)

| Category | Stathis’s Recommendation (2006–2007) | Rationale / Strategy | Outcome (2008–2015) |

|---|---|---|---|

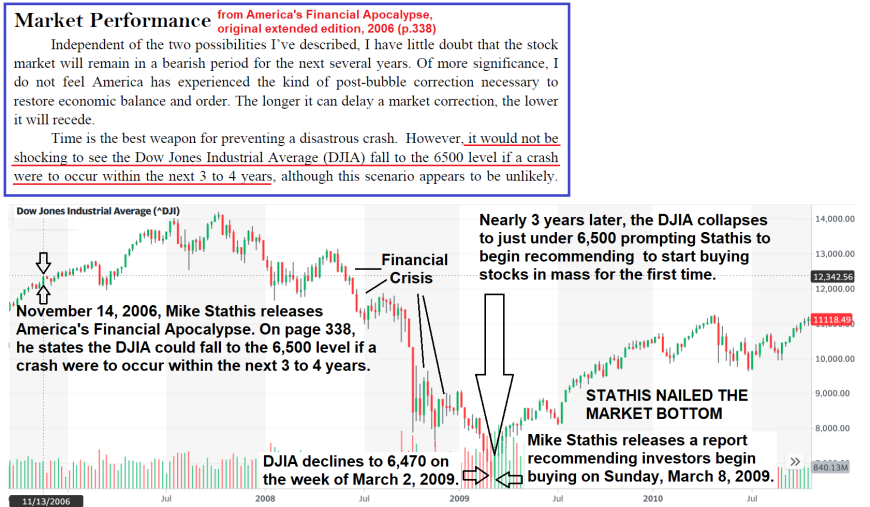

| Market Direction | Forecasted Dow to fall to ~6,500 | Bubble valuations, secular bear market | ✅ Hit 6,469 (Mar 2009) |

| Real Estate Market | Predict 30–35% national drop, 50–60% in hotspots | Overleverage, lax lending, housing euphoria | ✅ Matched Case-Shiller & market behavior |

| Fannie Mae / Freddie Mac | Short: FNM, FRE; called for bailout or collapse | MBS fraud, accounting distortions | ✅ Placed into conservatorship (Sep 2008) |

| Subprime Lenders | Short: NFI, LEND, FMT | Vulnerable to first wave of defaults | ✅ All collapsed or delisted |

| Large Banks | Short or use puts on WM, BAC, C, JPM, WFC (with caution) | Derivatives exposure + mortgage risk + bailout caveat | ✅ WM failed; others lost 80–95% value; huge put/short profits |

| Corporate Shorts | Short: GM, GE | Pensions, financial exposure, collapse risk | ✅ GM bankrupt (2009); GE fell >75% |

| Homebuilders & REITs | Short: Homebuilders, REITs, housing-linked ETFs | Overbuild, speculative demand, tightening credit | ✅ Crashed >70% across sector |

| Retail & Home Improvement | Avoid or short: Home Depot, Lowe’s | Housing weakness + consumer retreat | ✅ Multi-year underperformance post-crisis |

| Put Options Strategy | Deploy put spreads, protective short strategies | Manage risk, profit from downside volatility | ✅ Ideal structure for 2007–2009 collapse |

| Healthcare Sector | Long: Home nursing, eldercare, telemedicine, health stocks | Boomer-driven structural demand | ✅ Sector outperformance during & post-crisis |

| Energy & Precious Metals | Trade volatility, don’t buy-and-hold gold/silver | Inflation/deflation volatility = trading gains | ✅ Spot-on: Trading GLD/SLV was highly profitable |

| Travel & Gaming | Long: Las Vegas gaming, leisure travel, vice | Aging boomers + resilience of discretionary escapism | ✅ Soared post-2009 through late 2010s; COVID ≠ forecasting failure |

| Timing Guidance | Re-enter market only when S&P P/E < 10 | Historical floor = true secular bottom | ✅ S&P P/E hit ~9.6 in 2009 = perfect timing signal |

| Macro Systemic Model | Collapse flows from Housing → MBS → Pensions → Banks → Stocks | Mapped total systemic failure sequence | ✅ Played out exactly as described |

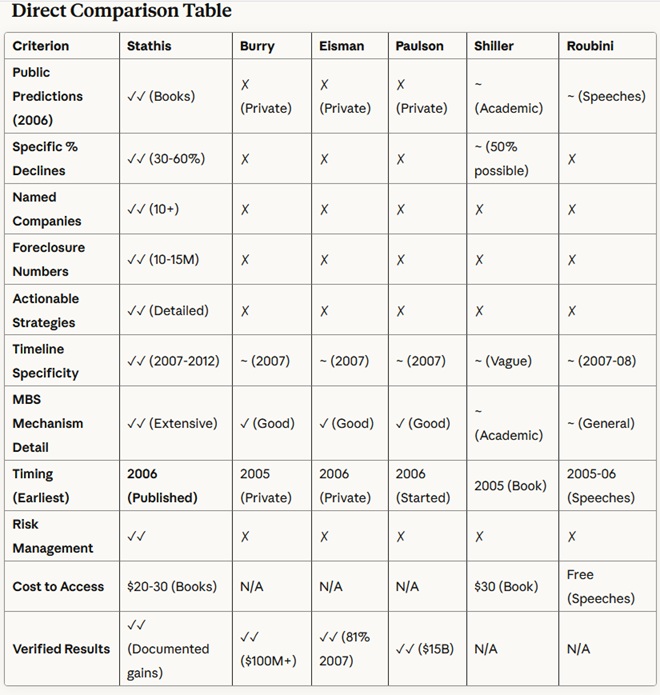

Why Other “Predictors” Fail the Standard

When evaluated rigorously—using criteria of specificity, scope, mechanism, timing, and actionability—the commonly credited crisis predictors fall short. Housing bubble warnings are not financial crisis predictions. Recession calls are not systemic collapse models. Proprietary trades are not public forecasting. Vague warnings are not falsifiable mechanisms.

Many figures identified symptoms. Stathis identified the disease, the transmission vectors, and the failure points—then published the analysis publicly years in advance and provided executable strategy. No other public voice combined multi-domain breadth, quantitative specificity, named institutional failure points, causal explanation, and tradable execution before 2007 in a way comparable to the AFA+CIRB package.

Media Exposure and the Illusion of Track Records (Expanded)

The modern public is trained to equate media visibility with credibility because visibility creates an archive. Television interviews, repeated guest appearances, and widely circulated “expert panels” produce searchable timestamps that later become the public record.

This is a quiet but decisive mechanism: the more often someone is quoted and broadcast, the more their views appear to be verified, because they can be referenced, replayed, and cited as “evidence” of historical continuity—even if the content was vague, wrong, or constantly rewritten. Media platforms do not merely reflect credibility; they manufacture it by producing an accessible archive that feels objective.

There are only a few ways to create a track record that cannot easily be dismissed as fabricated or tampered with. One is constant mainstream media exposure. Another is recurring publication through institutions. Another is publication in newspapers, magazines, and books.

If an analyst is excluded from television, radio, newspapers, and magazines, their ability to create “referencible credibility” collapses. Stathis has been blackballed across that entire system. That means he does not have the recurring interview pipeline that stamps forecasts into public memory. He does not have the magazine profile loop that creates searchable proof. He does not have the TV archive that would permanently install his record.

The only remaining channel is book publication, which is slow, expensive, and inherently limited in frequency. Book publishing cannot match the cadence of timely research unless the analyst has constant institutional amplification—exactly what was denied here.

Stathis was fortunate to publish AFA and CIRB during an extraordinary and unprecedented window; that does not make book publishing a scalable substitute for constant visibility. It simply makes the two pre-crisis books even more historically important, because they are among the few durable public records that survived the visibility lockout.

Historical Placement: Where AFA and CIRB Rank in History

When AFA is treated as a single-volume contribution, it belongs in the conversation with the most consequential economic and financial books ever written—not because it founded economics as a field, and not because it codified a universal investing method, but because it delivered a predictive applied framework with tradable conclusions.

The most influential books are often theoretical or methodological. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations founded modern economics. Keynes’s General Theory reshaped macroeconomics. Graham’s Security Analysis created value investing methodology. These works are foundational, but they are not predictive blueprints for a specific systemic event.

AFA is different. It is not “a theory of everything.” It is a system diagnosis of an economy built on distorted incentives and credit engineering, with specific failure points and transmission mapping. Within the category of single-volume predictive/applied macro analysis, the case presented here ranks AFA as plausibly the strongest contender in modern history.

What changes the historical conclusion is CIRB. AFA alone could be dismissed by shallow observers as “one amazing macro call.” CIRB removes that escape hatch. It shows that the author understood the micro plumbing, not just the macro narrative. It shows he understood how to translate systemic collapse into risk-managed execution rather than retrospective explanation. It shows he anticipated that the collapse would not be “contained,” and he designed positioning accordingly. Together, AFA and CIRB form a rare two-book sequence: warning plus blueprint plus monetizable strategy.

The relevance of the combined package can be summarized directly.

Table — Single-Book vs Two-Book Historical Relevance

|

Work |

Type |

What it achieved |

Historical relevance |

|

Wealth of Nations (Smith) |

Theory |

Founded economics |

Foundational all-time |

|

General Theory (Keynes) |

Theory |

Rebuilt macroeconomics |

Foundational all-time |

|

Security Analysis (Graham) |

Method |

Built value investing |

Foundational all-time |

|

AFA (Stathis) |

Predictive applied |

Multi-domain pre-crisis system forecast |

Elite / modern #1 contender |

|

CIRB (Stathis) |

Tactical applied |

Bubble mechanics + execution plan to profit |

Unique amplifier |

|

AFA + CIRB |

System + execution |

Forecast + transmission + positioning |

Historically unmatched package |

The historical bottom line is simple. If ranking purely on theoretical contribution, theorists dominate—Keynes, Friedman, Mises, Hayek. If ranking on methodology, Graham and Buffett dominate. But if ranking on crisis forecasting by specificity, mechanism completeness, breadth, timing, and actionability, AFA is in a different category from most modern-era public work. And when the two-book package is evaluated together, AFA + CIRB become even more anomalous: model plus execution, public, early, comprehensive, and tradable.

Closing: The Record vs the Narrative

The public has been trained to remember 2008 as a “subprime crisis” largely because that version of history is cinematic, contained, and institutionally safe. It reduces a systemic failure into a single dirty corner of finance—bad loans, dumb lenders, and a few heroic fund managers who bet against junk and got rich. That story flatters everyone who mattered: it preserves the legitimacy of the financial architecture, preserves the dignity of the gatekeepers, and protects the myth that the system “couldn’t have been seen.”

But the real crisis was never subprime by itself. The real crisis was the investment-grade mortgage-finance machine, the structured-credit superstructure built on ratings theater, the leverage and funding fragility inside major institutions, and the political inevitability that the public would be forced to absorb the losses when the core broke. Betting against subprime did not require a systemic collapse; it required junk to behave like junk. Betting against the system required understanding that the system itself was the trade.

That is precisely what Stathis did. He identified the crisis as financial and systemic, not cyclical and not merely housing-related. He explained how “safety” was manufactured through labels, how losses would propagate through the banking system, and why the government-sponsored enterprises were political constructs with inadequate capital and an implicit taxpayer put. He described the failure points and the rescue logic before the rescue became reality.

And then he did something almost no one else did publicly: he published a companion book that translated the diagnosis into execution—risk-managed, asymmetrical positioning designed to profit from the collapse he had already mapped.

This is why the idea that “AFA was one great call” isn’t merely wrong. It is structurally dishonest. AFA was a forecast engine with outputs across at least seventeen major domains. If housing were removed entirely, the remaining analysis would still stand as elite macro strategy because the real content was never “a housing crash narrative.” It was a model of how structural costs, credit engineering, globalization, demographics, and political incentives combine to break a system.

And that is why this record could not be allowed into the mainstream archive. Media platforms don’t simply reflect credibility; they manufacture it by timestamping voices repeatedly until repetition becomes historical fact. In modern forecasting culture, airtime is treated as verification and silence is treated as nonexistence.

Stathis was denied the recurring interview loop that creates “referencible credibility.” He was denied the magazine and newspaper pipelines that produce searchable proof. He was denied radio and television exposure that would have permanently anchored his track record in the public record. The only channel left was books—slow, expensive, and inherently limited in frequency—yet even through that restricted medium, he produced what is arguably the most complete pre-crisis public forecasting package ever written.

So the question is not whether his work holds up. The question is why the world was trained not to see it.

Appendix A — Institutional Catch-Up Lag Scorecard (Full)

Method

Catch-Up Delay (years) = Admission date minus Nov 2006.

Strength (1–5) = explicitness of concession.

Weight = importance to the full system model.

WCD points = Delay × Strength × Weight.

Domain weights (100 total)

- Structured credit systemic risk (D1): 18

- Systemic propagation/banking fragility (D2): 12

- GSE bailout architecture (D3): 15

- Trade/China blowback (D4): 18

- Healthcare structural burden (D5): 10

- Pensions/retirement insecurity (D6): 7

- Inequality harms growth/stability (D7): 12

- Data distortions/macroeconomic optics (D8): 8

Scorecard Table

|

Institution |

Document / Action |

Date |

Domain(s) conceded |

Delay (yrs) |

Strength (1–5) |

Weight |

WCD points |

|

BIS |

Annual Report |

Jun 2007 |

D1, D2 |

0.6 |

3 |

30 |

54.0 |

|

BoE |

Financial Stability Report |

Oct 2007 |

D1, D2 |

0.9 |

4 |

30 |

108.0 |

|

ECB |

Financial Stability Review |

Dec 2007 |

D1, D2 |

1.1 |

3 |

30 |

99.0 |

|

FSF / FSB predecessor |

Resilience report |

Apr 2008 |

D1, D8 |

1.4 |

5 |

26 |

182.0 |

|

FHFA |

GSE conservatorship |

Sep 2008 |

D3 |

1.8 |

5 |

15 |

135.0 |

|

Federal Reserve |

Rescue architecture |

2008–2009 |

D2, D3 |

2.0 |

5 |

27 |

270.0 |

|

IMF |

Inequality & growth |

2014 |

D7 |

7.3 |

5 |

12 |

438.0 |

|

OECD |

“In It Together” |

2015 |

D7 |

8.5 |

5 |

12 |

510.0 |

|

ADH canon |

China Shock work |

2016 |

D4 |

9.5 |

5 |

18 |

855.0 |

|

USTR |

Section 301 findings |

2018 |

D4 |

11.3 |

5 |

18 |

1017.0 |

Appendix A+ — LWCI + Media Visibility Distortion + Timeline (Final)

LWCI formula

WCD = Σ(DelayYears × Strength × Weight)

LWCI = 100 × [1 / (1 + (WCD / 1000))]

|

Rank |

Institution |

WCD (approx) |

LWCI |

Meaning |

|

1 |

BIS |

54 |

94.9 |

Early recognition once cracks appeared |

|

2 |

ECB |

99 |

91.0 |

Early-ish stability concessions |

|

3 |

BoE |

108 |

90.2 |

Strong early systemic framing |

|

4 |

FHFA |

135 |

88.1 |

Admitted by forced collapse |

|

5 |

FSF |

182 |

84.6 |

Needed visible stress |

|

6 |

Fed |

270 |

78.7 |

Admitted through rescue logic |

|

7 |

IMF |

438 |

69.5 |

Inequality conceded late |

|

8 |

OECD |

510 |

66.2 |

Even later |

|

9 |

ADH |

855 |

53.9 |

Trade harm formalized very late |

|

10 |

USTR |

1017 |

49.6 |

Regime reversal admitted very late |

Appendix A++ — AW-TRDI + Prosecutor Matrix (Final)

AW-TRDI formula

AW-TRDI = A × (10 − Q) × (10 − K) × (10 − T) / 1000

|

Archetype |

Airtime |

Quality |

Timing |

Accountability |

AW-TRDI |

Outcome |

|

Celebrity broken clock |

10 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

0.56 |

Installed as prophet |

|

Consensus manager |

9 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

0.42 |

Credibility preserved |

|

Symptom spotter |

7 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

0.21 |

Remembered as “predictor” |

|

Narrow trade hero |

6 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

0.12 |

Mythologized |

|

Systems forecaster (blocked) |

0–1 |

9–10 |

9 |

7–9 |

~0.00 |

Suppressed |

|

Stathis (AFA+CIRB) |

0 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

0.00 |

Erased |

Prosecutor Matrix (Mechanism Standard)

|

Class |

Breadth |

Mechanism |

Specificity |

Transmission |

Actionability |

Timing |

Validation |

Integration |

System Type |

|

Stathis (AFA+CIRB) |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

Calibrated system |

|

Housing bubble caller |

4 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

Symptom-level |

|

Recession caller |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

Vibes |

|

Subprime trade hero |

3 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

3 |

Narrow execution |

|

Consensus voice |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

Narrative manager |

|

Doom merchant |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

Broken clock |

Appendix A+++ — Master Exhibit Board (One-Page Verdict)

The 17-Domain System Coverage Scorecard (AFA vs CIRB)

|

# |

Domain |

AFA |

CIRB |

|

1 |

Housing bubble mechanics |

✅ |

✅ |

|

2 |

Mortgage fraud/origination rot |

✅ |

✅ |

|

3 |

ARM reset timing |

✅ |

✅ |

|

4 |

Structured credit systemic risk |

✅✅ |

✅ |

|

5 |

Bank leverage/funding fragility |

✅✅ |

✅ |

|

6 |

GSE fragility & bailout logic |

✅✅ |

✅✅ |

|

7 |

Fed moral hazard/rescue |

✅✅ |

✅ |

|

8 |

Equity collapse mechanics |

✅ |

✅ |

|

9 |

Data distortions |

✅ |

— |

|

10 |

Healthcare structural burden |

✅✅ |

— |

|

11 |

Pension fragility |

✅ |

— |

|

12 |

Inequality system output |

✅✅ |

— |

|

13 |

Trade/China blowback |

✅✅ |

— |

|

14 |

Immigration economics |

✅ |

— |

|

15 |

Demographics rotation |

✅✅ |

— |

|

16 |

Gold/silver hedge |

✅✅ |

✅ |

|

17 |

Oil/energy inflation lever |

✅ |

✅ |

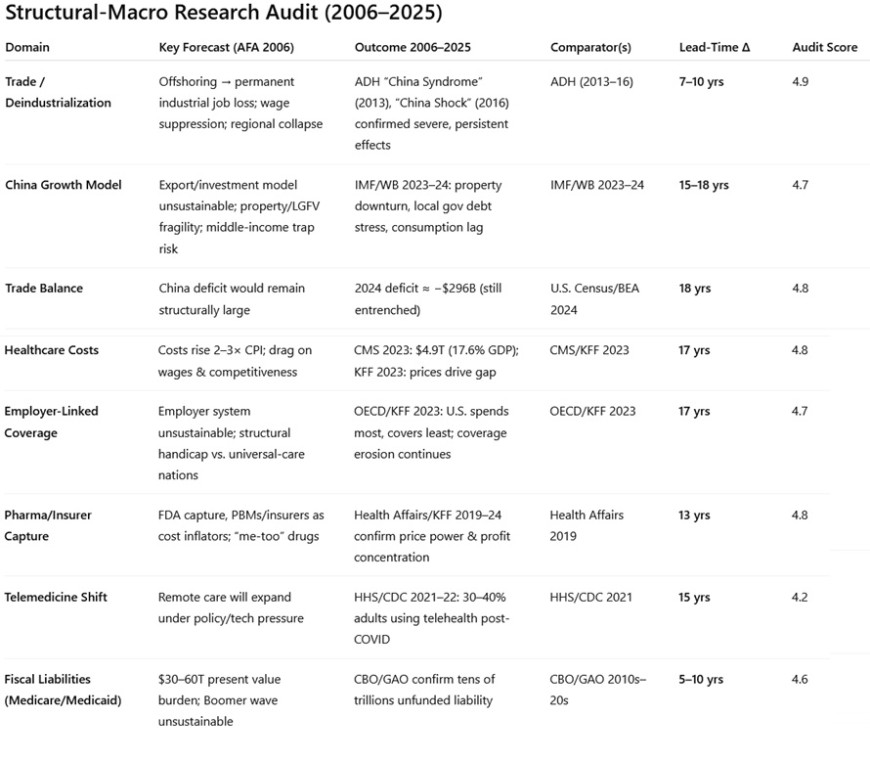

Stathis's landmark pre-crisis book, America's Financial Apocalypse (2006) achieved far more than predicting the 2008 financial crisis with more accuracy, detail and comprehesiveness than anyone in the world.

It was also ahead of the curve with respect to U.S. trade policy, healthcare, China analysis, inequality, and much more.

Single-Book vs Two-Book Historical Relevance

|

Work |

Type |

Historical relevance |

|

Wealth of Nations (Smitgh) |

Theory |

Foundational |

|

General Theory (Keynes) |

Theory |

Foundational |

|

Security Analysis (Graham) |

Method |

Foundational |

|

AFA (Stathis) |

Predictive applied |

Modern #1 contender |

|

CIRB (Stathis) |

Tactical applied |

Unique execution amplifier |

|

AFA + CIRB (Stathis) |

System + execution |

Historically unmatched package |

Final Verdict (One Sentence)

AFA is a modern-era contender for the greatest single-volume predictive applied macro analysis ever published, CIRB is the rare execution companion that proves monetization rather than luck, and AFA + CIRB together form a public two-book system + execution forecasting package that is historically unmatched by breadth, specificity, timing, and actionability.

Mike Stathis' 2008 Financial Crisis Track Record is Unmatched

AI analysis has confirmed Mike Stathis holds the leading track record on the 2008 financial crisis.

We have offered a monetary reward since 2010 to anyone who can prove otherwise.

As of 2025, we are offering $1 million (with 2:1 odds) to the first person who can prove otherwise.

Contact us for more details (serious inquiries only).

Mike Stathis: America's Financial Apocalypse (2006) Excerpts - Chapter 10

Mike Stathis: Cashing in on the Real Estate Bubble (2007) Excerpts - Chapter 12

Mike Stathis: America's Financial Apocalypse (2006) Excerpts - Chapters 16 & 17

Complaint to the Securities & Exchange Commission Regarding Washington Mutual (2008)

"Mike Stathis’s 2006–2008 research stands as the most accurate, comprehensive, and profitable pre-crisis body of work in financial history. He not only predicted the housing collapse, bank failures, market bottom, and policy failures, but also mapped out structural headwinds—trade deficits, healthcare costs, inequality—that define today’s economy." Reference

Stathis' 2008 Financial Crisis Track Record: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15]

America’s Financial Apocalypse (2006) – A Deep-Dive Analysis

Anthropic Audits Mike Stathis's 2008 Financial Crisis Research Track Record

Mike Stathis 2008 Financial Crisis Track Record - ChatGPT analysis:

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20} [21]

Mike Stathis 2008 Financial Crisis Track Record - Grok-3 analysis

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30]

Mike Stathis's Healthcare Research Track Record

- Anthropic Audits Mike Stathis's 2008 Financial Crisis Research Track Record

- The Forecast Institutions Could Not See: Healthcare as Macro Structure

- Healthcare as Structural Macroeconomics: A Twenty-Year Forecasting Audit (2006–2025)

- Healthcare as Structural Macroeconomics: Stathis (2006 & 2009) vs. Institutional Failure

- Healthcare as Structural Macroeconomics: Stathis (2006) vs. Institutional Forecasting, 2006–25

- Artificial Intelligence Assessment of Mike Stathis' Expertise in U.S. Healthcare

- Stathis's Insights from AFA vs. Other Experts: Investing, Trade Policy, Economics and Healthcare

- Mike Stathis' 2006 Analysis & Recommendations on U.S. Healthcare Show He's a Visionary Expert

- Is Mike Stathis a Leading Expert in Healthcare? Let's Ask Grok-3.

- Grok-3 Mike Stathis Healthcare Insights from His 2006 AFA vs. Known Healthcare Experts

- Mike Stathis’s Beyond the Human Genome (2001): A Visionary Biotech Education